Move fast and break things.

It is Mark Zuckerberg’s (in-)famous motto for design and management process: to disrupt existing normality, to get rid of unnecessary formalities and red tape, to deliver faster to the hands of customers. This ideology sounds enticing and may be pertinent to keeping processes and management lean. It has been supported by the proliferation of start-ups. Nevertheless, being fast and breaking things does not guarantee a good outcome all the time. Being fast pushes us to process fast; processing fast invites us to jump steps; jumping steps risks committing mistakes—sometimes unnecessary, consequential, and unmendable ones.

To avoid breaking dishes (and perhaps a product/brand/company’s reputation and people’s trust in return), we might have to slow down at times—especially at crucial moments when we make decisions and/or judgement calls. We would have to acknowledge our limits and wisely cope with them.

This is what Thinking, Fast and Slow by Daniel Kahneman is about: understanding the limits of our mind, acknowledge them in our thinking, and wisely cope with them as they happen.

Below I am going to unfold some of my highlights from the book related to my profession as an Experience Designer. I warn you: it is looooong. TL;DR is here:

- We are lazy in thinking. Most of the time, we just follow our ‘instinct’.

- We only know what is available for us to know. The unknown can affect (hugely) what we are evaluating, judging, and designing.

- We circumvent complicated problems by answering easier, relatable questions.

- We are prone to what we are used to believing. Taking action simply based on our beliefs can adhere us further (only) to them.

- Experience does not mean memory, vice versa. Which one are you talking about?

0. How do we think?

At ground zero, Kahneman points out that there are two distinct thinking systems in our minds. ‘System 1’ is mostly autonomous and capable of making fast, intuitive decisions. It is partly rooted in our evolutionary instinct and, to a certain extent, developed through the years from how we experience and learn about the world. ‘System 2’ is the slower counterpart. It monitors System 1 and is capable of producing deliberate thoughts. By default, it is idle, remains comparatively dormant, and requires effort to wake it up. These two systems coexist and spontaneously interfere with each other without us becoming aware of such an occurrence. In the book, Kahneman analyses the interrelations between the two systems. Examples about cognition and thinking procedures are in plenty and well detailed to aid in discerning the intricacies of their correlation. Here are a few tricky discoveries of cognitive biases, which can apply to the Design & Research environment.

1. ‘What you see is all there is.’

Our decisions are based on our judgements. Our judgements are based on our understanding. Our understanding is based on our perception. And our perception is based on what there is—in front and around us—the discoverable.

Simply put, we know the things we’ve learnt of; and we do not know what we have not. Hence, when we have to make decisions and judgements about something beyond what we know, we turn back to what we have learnt and memories of how we’ve applied it. We search through our experiences and weigh our options against what we have lived through and believe. We seek to correlate fragments to form our current understanding of dos and don’ts.

But there is a lot more than what we know, beyond our understanding, beyond our awareness, and even just beyond the discoverable (e.g. until the current time). Of course, you may look up online or in books when you have some necessary clues as to what you’re missing. But when these clues are not in our vision, we simply won’t know them or their impact on the subject matter and the decision at hand.

You may observe a wilting and yellowing plant and link it to your understanding that it may have been under-watered. Not until you learn that it could be a symptom of rot roots or bound roots would you enquire into its bottom soil. And all this very likely has started to happen before you can even see the plant wilt. Similarly, you may observe a drop in sales in your smartphone product line and begin to look back in history how products and their sales figures were revamped. You may well infer that making a trendier and fancier look for the next generation would help restore its desirability. But not until you realise that your customers have turned to durability and sustainable ethics can you take the right track towards a proper solution.

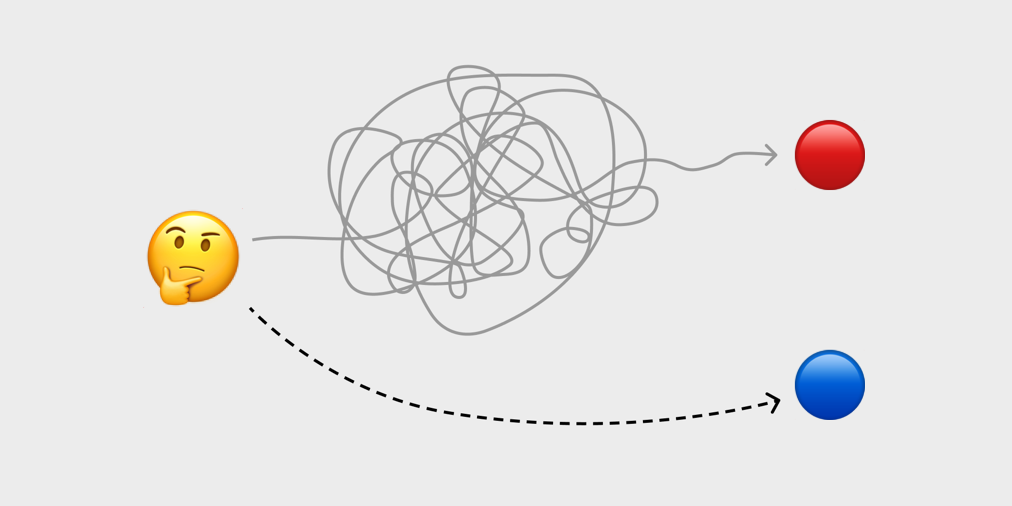

2. We replace complex problems

When we are dealing with complex problems, Kahneman points out that we often dodge them by replacing them with simpler, more straightforward questions, answering the substitutes, and then pretending to have resolved the original ones. This swapping mechanism is so automated and rooted in our thinking that we do not even notice it when we have performed it.

Take an example: You just relaunched a website, and you want to assess how great your website is. You approach some visitors and ask them whether your new website is great. While they may tell you they like the new fresh look or they prefer the old one, and point out all the wows and ewws, they might have already been answering the substitute question ‘Do I like this new website?’, instead of ‘Is this new website great?’.

To really evaluate whether your new website is great or not, you might have to guide yourself through a few criteria and metrics:

- Does it allow better information access (usability)?

- Does it offer more engaging storytelling (branding)?

- Does it drive better e-commerce conversion (sales)?

- Does it satisfy a broader coverage of use cases for all visitor profiles (accessibility)?

- Does it load faster on poor Internet connection (performance)?

All in all, you are determining whether it better fulfils your original objectives than the old website, and/or whether it attains higher scores in the parameters that you measure. Thus, it is crucial to trace qualitative feedback back to where they come from, to what they are really addressing; and then compare whether and how much they are in line with your assessment before jumping into conclusion.

3. We create illusion to validate what we believe

When we think, not only are our minds lazy and prone to inertia, limited in scope, and erratic along the route, what’s more is that our mind is also delusive regarding the basis on which we think.

In his book, Kahneman has cited many cases about experts failing their own expertise. The situation is intriguing to study. The objective discovery from this is that our beliefs—the collection of good-and-bads through experiences, and the pedestal of current judgements and decisions—are not often based on facts; but rather on stories and their coherence.

When we hear a story, we evaluate whether the story makes sense, whether it sounds plausible. The further we listen, we analyse whether the information is consistent—consistent with the idea conveyed, consistent with what we were told before—and maybe whether the interlinkages sound admissible. The more complete the story is, the more plausible it appears to us. If nothing raises concern to our guard (System 2), we do not necessarily attempt to seek whether what we are hearing/seeing is true; we do not verify it by reflex.

This is particularly dangerous as how social media and partisan (at times fake) news have demonstrated. The former gradually sets us into our own bubble through (micro-)profiling; the latter creeps in and reinforces the echoes in the chamber. The more resounding a story seems, the more we may believe it; the more we interact with the things we believe, the more we tend to get profiled as interested in that topic; thus the more we get shown that content… Echoing algorithms and potential dogmatism in short.

As designers, how can we help solve this problem? How can we help people step out of their chamber? How can we prevent polarising communities and help people discover pluralities in perspectives and opinions? These problems are nothing new, but counteractive measures continue to fall short.

Unravelling these puzzles would require better initiatives from involved groups as collectives (designers + developers, content creators + visitors + media regulators, business managers + entrepreneurs + legal bodies, …) to undertake a closer, introspective collaboration for dissolving our illusions of verities.

4. We do not tell the same experience as we experience it

Last but not least, what makes our mind more complicated is the construction of scenes which we underwent inside our head—called memory.

When we recall an experience, we do not necessarily paint the same picture as to how we experienced it. This is not about accusing us of a lying nature, but rather about the deviation in the image we create relative to how we truly lived the event. And through establishing this image (later as memory) in our mind, which we will remember over time and tell, we neglect the details to a certain extent and change the overall scenery inscribed in our head.

You may be on a holiday. Everything is pleasant and fine. Until the point where you lose your wallet and your experience takes a 180 ̊ turn into a frantic nightmare. Later on, when your friends ask how your holiday was, your narration will very likely be dominated by the peak moment of the holiday (unfortunately your lost wallet) and how it ended. Your memory of this holiday would very probably also be affected by the incident.

Kahneman explains that memory (the mental notation of how something happened) is symbolised by the peak and the end of an experience. Other details tend to wane when we are reporting the occurrence. Besides, the amount of time in total matters little when we gauge it in hindsight. Our retrospective evaluation of an event can almost be summarised by the average of the most sensational moment and the end of the entire encounter.

It opens up a big question for Experience Design: What are we actually designing for? Are we designing for a better in situ experience as we live it at the very moment, or are we designing for a better memory of the experience afterwards? The real situation may be less philosophical than the question appears. The best is to maximise both.

If you file a tax declaration online, the interface should:

- Convey security and confidentiality when you are using it (experience security);

- Enable you to get yourself through the filing process without too much doubt (experience ease); and

- Offer less hassle than paper and pen—and quick (experience convenience)!

We can offer you detailed explanations of all the form fields through your preparation for the tax declaration. In this way, you may experience ease from the platform when using it, as you have never been provided such clear guidance and pinged by so few doubts. However, this will probably lengthen your preparation before you can submit your file because it now consumes your attention and patience at every granular level. You would not experience convenience. It might even give rise to a repelling sensation within your quick-to-associate mind, that this platform is the devil of bureaucracy incarnate. You would detest this platform and label it in your memory as ‘never use again’.

Tricky is the way we think, trickier than we know it and are aware of it. There are many more unfamiliar bizarreries in our minds, side tracks and loopholes in our thinking. To really understand the limits of our cognitive process so as to acknowledge and better cope with them, I invite you to read Kahnemann’s book itself! 😉 You will very likely discover the commonly overlooked mistakes/biases related to your own field/practice.

To recap:

- We are lazy in thinking. Most of the time, we just follow our ‘instinct’.

- We only know what is available for us to know. The beyond can affect what we are evaluating, judging, and deciding.

- We circumvent complicated problems by tackling easier, relatable issues.

- We are prone to what we are used to believing. Actions taken simply based on our beliefs can make our grip further tenacious.

- Experience does not mean memory, vice versa. Which one are you talking about?

This article is also published on Medium.